Projects of Survival

In the early months of the Great Depression, Herbert Hoover was fond of saying: “Prosperity is just around the corner.” At the same time, millions were losing their jobs, facing utility shut offs and evictions, moving into tent encampments and shantytowns, and standing in bread lines for hours. In 1929, there was no public social safety net or welfare programs. Instead, the state’s response was to support Wall Street while directing the poor toward an intolerant patchwork of religious and private relief organizations.

Left to make ends meet from scraps of a charity system, many poor and low income people took survival into their own hands. They marched in unprecedented numbers against hunger and unemployment, led daring wildcat strikes and other militant actions from industrial plants in the Midwest to tenant farms in the Delta, and created mass organizations like the Unemployed Councils. These multi-racial Councils developed in cities across the country around relief for unemployed workers, overturning thousands of evictions and utilities shutoffs. They worked locally to address their immediate needs, but in the early years of the Great Depression they also became a political home for tens of thousands of poor people. Central to the Councils’ vision was political education, leadership development, and larger forms of collective agitation.

Just a few years later, the Social Security Act and other major government programs were created. Franklin D. Roosevelt and a handful of “transcendent” politicians often recieve credit for the Act, but it was the collective efforts of the masses that forced the government into action. Roosevelt did not dream of fundamental change for the poor; by the end of the 1930s, the New Deal was a constrained political project that saved American capitalism from itself. The more sweeping anti-poverty provisions of the Deal were, instead, the result of poor people taking action together.

Today, we confront another economic crisis amid authoritarian creep. Five years have passed since the coronavirus pandemic began, revealing and exacerbating long-standing fissures in our society. Despite large federal investments in public assistance, systemic inequities have stopped millions of people from receiving adequate care and protection from the virus’ tragic path. This means the virus harmed (and continues to harm) people unequally by income, race, ethnicity, gender, ability and geography. Collectively, we have not grappled with the extraordinary effects of this societal failure: over 1.2 million people have died from COVID-19 in the US, more than any other country, while millions more labored dangerously on the frontlines of the pandemic.

In response to these failures, thousands of communities stepped up to provide critical care for their families, friends and neighbors. While these networks were not new, their scale and scope during the pandemic was. On one hand, these survival activities were an inspiring reminder that people in crisis will always find ways to take care of each other. On the other hand, the extent to which these activities were necessary showed the widespread and punishing reality of American poverty and inequality.

In the five years since the onset of the pandemic, these inequalities have only grown along with the need for survival organizing. In this time, we’ve witnessed huge redistributions of wealth from the poor to the ultra rich. According to the Institute for Policy Studies, billionaires have nearly doubled their wealth since 2020 – adding 2.6 trillion to their combined value. Meanwhile, more than 40 percent of the population — about 140 million people — live in poverty or on the verge of it. Between long-COVID, ongoing spread of the virus, higher disability rates, and other permanent changes to how we live, learn, worship, and work, the pandemic is still being felt. And yet, the federal government is poised to remove millions of working class Americans from their needed housing, healthcare, and food assistance programs. This threatens the lives and livelihoods of an ever-growing swathe of vulnerable Americans. In other words, Prosperity for most Americans is not “just around the corner.”

In fact, the community-based networks that burst to the fore during the early years of the pandemic are still providing support to millions of people every day, responding to multiple ongoing crises around housing, hunger, health care, and climate breakdown, as well as attacks on immigrant communities, reproductive rights, and LGBTQ+ youth and households.

For more information about survival organizing since 2020, explore our latest policy report: A Matter of Survival.

Mutual aid has become a project of rejecting and resisting the state and its decrepit and hateful institutions; this is a posture that claims that no one is coming to save us, that our communities have all that we need, and that we can transform our conditions by coming together through networks of social solidarity.

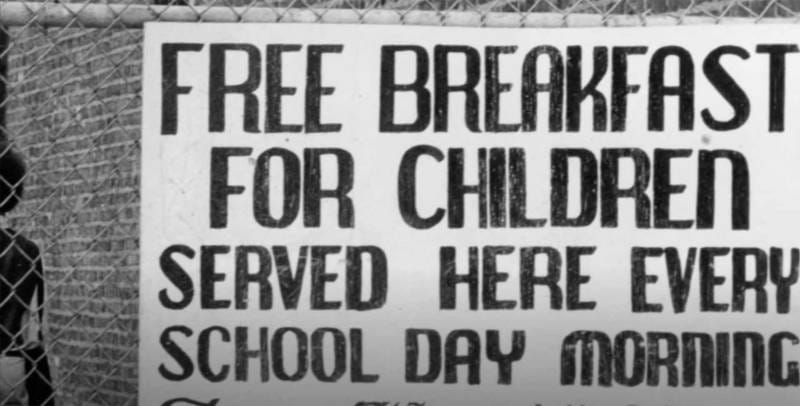

What, then, does this moment require of us? In the last 5 years, many have turned to history to better understand how people have responded to similar crises in the past. Many have looked to the 1920s and 1930s because of the simultaneous economic collapse alongside the widespread rise of fascism. Others look to the 2000s and the 2008 financial crisis. We look to the Black Panther Party’s free breakfast program in the early 1970s. The free breakfast program has recently been lifted up as a leading model of mutual aid; one popular narrative is that the free breakfast program, which fed tens of thousands of children, is a key example of how marginalized communities care for themselves in the absence of and counter to the state.

What is forgotten is the political orientation of the breakfast program, which moved beyond the realm of mutual aid as we often understand it. The Panthers initiated the program not just to feed people, but to actively and purposefully demonstrate the failures of Johnson’s War on Poverty and the contradictions of a nation whose enormous wealth — and enormous racism — was increasingly being marshaled to hurt and impoverish a majority of people at home and around the world. At the onset of a new and regressive world order, the Panthers saw their programs as a way to build a movement that could spark larger political change. This meant that all of their community work was interwoven with deep political study and analysis, highly visible protest, sophisticated communications and cultural organizing, and a commitment to sustaining leaders who could stick and stay for the long-haul. And while deeply rooted in poor black urban communities, the Panthers also inspired and connected with similar efforts of Latino and poor white organizations, as well as efforts of the poor in other parts of the world.

These were treacherous waters. At the time, J. Edgar Hoover and the FBI listed the Black Panthers and their breakfast program as “the greatest threat to internal security in the country.” The government recognized that the program represented the kind of survival organizing that could catch fire across the wide populations of poor and dispossessed people who had been abandoned by the War on Poverty and a hyper-racist society. The Panthers’ ability to demonstrate this abandonment, unite leaders within their communities, and build relationships with poor people across lines of division was a weapon far more powerful than the guns they carried. If these programs had just been a question of direct service or insular mutual aid, the government wouldn’t have hunted the Panthers down. They would have simply ignored them.

In the early 1990s, as homeless leaders with the National Union of the Homeless were taking over vacant, federally owned housing, they studied the experience of the Panthers. In that history, they saw revolutionary leaders beginning to understand that in order to end their suffering, they would need new forms of organization that could confront the government and the ruling class head on. During these housing takeovers, homeless leaders identified “The Six Panther Ps”, lessons that they drew from that history: 1. Program 2. Protest 3. Projects of Survival 4. Publicity Work 5. Political Education 6. Plans not Personalities. These organizing cornerstones, they explained, were inseparable from one another. There needed to be a political program — a vision and set of values — that was built through direct action, strong communications, political education, leadership development, and a politicized and militant form of mutual aid that the Homeless Union called “Projects of Survival.”

They explained:

Our organizing attracts people on the basis of their immediate needs — food, housing, childcare, etc. Activities like tent cities and housing takeovers are designed to meet people’s needs and build organization in the process. As we come together to meet our common needs, opportunities for political education and other key elements arise. We have tremendous strength by virtue of addressing the problems which people are struggling with day-to-day. However, we don’t just try to meet people’s individual needs — we use that struggle to fight for everyone’s needs to be met.

The Homeless Union emerged as a response to the explosion of homelessness in the 1970s and 1980s, as the government demolished public housing and funded urban development projects that fueled gentrification. Poor and homeless communities quickly began to organize. They opened their own shelters and led takeovers of vacant houses owned by the Department of Housing and Urban Development, because there were more houses sitting empty than there were homeless people. These were their projects of survival: they secured housing and the other resources necessary to fuel the birth of a movement to end poverty, led by the poor. As they began to win new protections and expanded rights for their communities, their slogan became “Homeless not Helpless.”

In 2020, in the midst of a pandemic that reshaped our world, we saw powerful projects of survival sprout all over the country. In the first few weeks of the virus, poor people in a number of cities won moratoriums on evictions and utility shutoffs. In Detroit, the People’s Water Board, Michigan Welfare Rights Organization, and others forced the city government to enact a moratorium on water shut offs and to turn water service back on for $25. For them, this is a short-term victory that is connected to their decades-old fight around the right to water and the welfare system. In Northern California, Moms 4 Housing and the California Homeless Union took over vacant houses and organized to protect tent encampments as they carried out groundbreaking political work among the homeless. Further south, the Los Angeles Tenants Union, made up of neighborhood organizations of the poor, lept into action to care for their communities while also echoing the call for a rent strike that resounded across the country.

Projects of survival do many things: they meet the needs of people who can then come into new political consciousness; they encourage and secure leaders who have a sense of their own agency and political clarity; they connect to political programs that rely on many different tactics and strategies; they expose the larger society to the moral failures and contradictions of governing systems; and they make demands and claims on the power of the state. Those who take up projects of survival are the first to feel the pain of injustice and the first to sound the alarm against it. They take action from a position of necessity and life-or-death struggle: this emerges organically as people do what they need to survive, but also requires deep strategy and the collective genius of whole communities of people to secure those needs. At the very core, these projects are woven into a political and moral imagination that emphatically believes in the power of poor people to be agents of change, not just subjects of a cruel history.

There are many such examples of these projects of survival in US history. The Unemployed Councils and other organizing efforts during the Great Depression could have been called projects of survival; a hundred years earlier, the Underground Railroad could have as well. The decades-long work of those escaping bondage, and of their compatriots in free states, met the dire needs of many and challenged the economic, political, and ideological systems of slavery. The revolutionary motion of hundreds of thousands of people smuggling themselves out of slavery ignited a movement whose material and moral intervention was irrefutable by the 1850s. Because of these leaders, no one in the country could be neutral on the question of slavery and, although half the nation may have disagreed, there could and would never be a return to “normal.”

The most critical element of projects of survival is the regular work of meeting unmet needs. However, material support alone is insufficient to anchor an organized social movement. Instead, this activity must be politicized, coordinated and developed at scale, with its participants trained and willing to exert political leadership and direction for the whole of society.

And yet, this extensive survival organizing remains on the margins of the social justice movement landscape. Little attention is paid by national organizations, foundations, policymakers, and others to the networks of care that hold together thousands of communities. Even less attention is paid to the possibility of leveraging these emerging “projects of survival” into footholds to anchor a broadbased movement of poor and dispossessed people that can turn these activities into political demands of our government and society at large.

In this moment of widening poverty and inequality, the leadership we desperately need will not come from the rich, from corporations, or from nonprofit models that provide triage but do not demand change. If we are to build a nation that cares for all people, it will be through the leadership of hundreds of thousands of politicized poor people and mass organizations of the poor. It will be because of leaders who recognize that the only way to break free of the bitter cycle of simply surviving is through a broad movement of the poor and dispossessed that can rally our society into action.

Some have argued that through this disaster we cannot allow a return to normalcy, that normalcy never worked for the majority of people anyway. But the truth is that normal no longer exists. The order of the past is gone. Now the only direction is forward, and it will be the poor already standing in the breach of the old wounded world who will help usher us into the new.